Folate is the generic term for vitamin B9 compounds that act as coenzymes in one‑carbon transfer reactions necessary for de novo purine and thymidylate synthesis and for remethylation of homocysteine to methionine. Natural food folates (mostly reduced tetrahydrofolate polyglutamates) and synthetic folic acid (oxidized monoglutamate used in fortified foods and supplements) are jointly referred to as folate in nutrition policy and labeling (NIH Office of Dietary Supplements).

Chemistry and nomenclature

Folate encompasses multiple biologically interconvertible forms based on tetrahydrofolate (THF), including 5,10‑methylene‑THF and 5‑methyltetrahydrofolate (5‑MTHF). Folic acid is the fully oxidized, stable monoglutamate form used in fortification and most supplements; some supplements provide 5‑MTHF, but standardized dietary folate equivalent (DFE) conversion factors for 5‑MTHF are not formally established in U.S. reference standards (NIH Office of Dietary Supplements). These folate coenzymes fuel One-carbon metabolism critical to nucleotide synthesis and methylation biology (

Journal of Nutrition).

Biochemical functions

Folate coenzymes donate one‑carbon units for purine synthesis and for the thymidylate synthase reaction converting deoxyuridylate to thymidylate, supporting DNA replication and repair. Folate also supplies 5‑MTHF for methionine synthase, enabling remethylation of homocysteine to methionine and generation of S‑adenosylmethionine, a universal methyl donor for DNA, RNA, protein, and lipid methylation (NIH Office of Dietary Supplements;

Frontiers in Oncology). Disruption of these reactions underlies megaloblastic changes in rapidly dividing tissues and can elevate plasma homocysteine (

NIH Office of Dietary Supplements).

Absorption, transport, and metabolism

Dietary folate polyglutamates are deconjugated to monoglutamates in the proximal small intestine and absorbed primarily via the proton‑coupled folate transporter (PCFT; SLC46A1), with additional transport by the reduced folate carrier; pharmacologic folic acid can also cross by passive diffusion. Loss‑of‑function variants in SLC46A1 cause hereditary folate malabsorption, establishing PCFT’s central role in intestinal uptake (Cell). After absorption, folate is reduced by dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) to THF and converted into methyl and formyl derivatives; the major circulating form is 5‑MTHF. Total body stores are ~15–30 mg, about half in the liver, with enterohepatic cycling (

NIH Office of Dietary Supplements).

Dietary sources and bioavailability

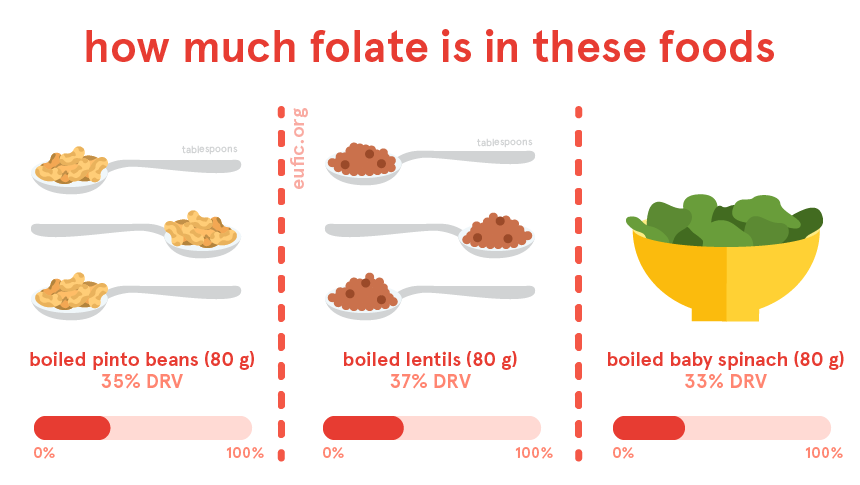

Naturally folate‑rich foods include dark green leafy vegetables, legumes, liver, asparagus, and citrus juice. In the United States, folic acid fortification of enriched cereal grain products at 140 μg per 100 g became mandatory in January 1998 to reduce neural tube defects, and in 2016 voluntary fortification was permitted for corn masa flour (safe use level 0.7 mg folic acid per pound of corn masa flour) (NIH Office of Dietary Supplements;

United States Food and Drug Administration). Because folic acid is more bioavailable than food folate, intake recommendations are expressed as dietary folate equivalents (DFE): 1 μg DFE = 1 μg food folate = 0.6 μg folic acid from fortified foods or supplements taken with meals = 0.5 μg folic acid on an empty stomach (

NIH Office of Dietary Supplements). On U.S. Nutrition Facts labels, folate is listed as mcg DFE, with any folic acid content shown parenthetically (

FDA, labeling guidance).

Requirements and assessment

The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) is 400 μg DFE/day for adults, 600 μg DFE in pregnancy, and 500 μg DFE in lactation. The Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) for folic acid from fortified foods and supplements is 1,000 μg/day for adults; no UL is set for naturally occurring food folate. Serum folate reflects recent intake, whereas erythrocyte folate reflects longer‑term status. At the population level, the World Health Organization recommends red blood cell folate concentrations above 400 ng/mL (906 nmol/L) in women of reproductive age to achieve the greatest reduction in neural tube defects (NIH Office of Dietary Supplements;

WHO guideline;

CDC summary).

Reproduction and neural tube defects

Periconceptional folic acid supplementation lowers the risk of neural tube defects (NTDs) such as Spina bifida and anencephaly. In high‑risk women with a prior NTD‑affected pregnancy, folic acid reduced recurrence by about 70% in the multicenter MRC Vitamin Study (MRC Vitamin Study, Lancet). Public health guidance in the United States recommends daily folic acid (0.4–0.8 mg) for all who could become pregnant, beginning at least one month before conception and continuing through the first 2–3 months of pregnancy, because neural tube closure occurs early—typically 26–28 days post‑fertilization (

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force). Following U.S. grain fortification, population NTD prevalence declined, with early national surveillance indicating substantial reductions in spina bifida and anencephaly (

JAMA;

CDC MMWR).

Cardiovascular and other health outcomes

Because folate lowers homocysteine, trials have evaluated whether folic acid reduces cardiovascular events. Meta‑analyses show a modest reduction in stroke risk overall, with benefit most evident in primary prevention and in regions without folate fortification, while effects on coronary heart disease are null; results vary by baseline folate status and homocysteine reduction (Stroke meta‑analysis;

Journal of the American Heart Association;

Public Health Nutrition).

Deficiency and clinical features

Folate deficiency impairs DNA synthesis, producing megaloblastic (macrocytic) anemia and glossitis; neuropsychiatric symptoms can overlap with vitamin B12 deficiency. Laboratory evaluation typically includes serum and red blood cell folate and homocysteine, with attention to ruling out Vitamin B12 deficiency to prevent neurological harm (StatPearls;

NIH Office of Dietary Supplements). Groups at increased risk include individuals with alcohol use disorder, malabsorptive conditions, increased requirements (e.g., pregnancy), certain genetic polymorphisms affecting folate enzymes, and users of medications that interfere with folate metabolism (

NIH Office of Dietary Supplements).

Drug–nutrient interactions and antagonists

Antifolate chemotherapeutics (e.g., Methotrexate) inhibit DHFR; supplemental folate or folinic acid is used cautiously in non‑oncologic low‑dose regimens to reduce toxicity but can counteract antitumor efficacy in oncology settings. Several antiepileptic drugs (phenytoin, carbamazepine, valproate) lower serum folate and may interact with supplementation; sulfasalazine reduces intestinal folate absorption. Management should be individualized by indication and specialty guidance (NIH Office of Dietary Supplements).

Safety considerations

High folic acid intake can correct hematologic abnormalities of unrecognized vitamin B12 deficiency while allowing neurologic injury to progress; concerns also include potential effects of unmetabolized folic acid and promotion of pre‑existing neoplastic lesions, though evidence is mixed. U.S. ULs therefore apply to folic acid from fortified foods and supplements (1,000 μg/day for adults), not to naturally occurring food folate (NIH Office of Dietary Supplements).

Public health policy and fortification

Food fortification is a population strategy to raise folate status when periconceptional supplementation coverage is incomplete. The U.S. mandated folic acid fortification of enriched cereal grains in 1998 and later permitted fortification of corn masa flour to reach populations consuming corn‑based staples (United States Food and Drug Administration;

NIH Office of Dietary Supplements). Ongoing surveillance and RBC folate monitoring inform program performance, consistent with WHO recommendations (

WHO guideline;

CDC MMWR).

Measurement and laboratory cutoffs

Serum folate adequacy in clinical practice is often defined as >3 ng/mL, while erythrocyte folate >140 ng/mL reflects longer‑term sufficiency; for NTD prevention at the population level, WHO recommends RBC folate >400 ng/mL (906 nmol/L) in women of reproductive age, with microbiological assay preferred for comparability (NIH Office of Dietary Supplements;

WHO/NCBI Bookshelf).

Historical milestones and evidence base

Key evidence includes randomized trials demonstrating prevention of NTD recurrence by folic acid (MRC Vitamin Study) and subsequent policy actions mandating fortification, followed by observed declines in NTD prevalence in national surveillance (

JAMA;

CDC MMWR). Molecular elucidation of intestinal folate absorption via PCFT (SLC46A1) provided mechanistic insight and explained the phenotype of hereditary folate malabsorption (

Cell).