Origins and Development

Impressionism emerged in France in the mid-19th century as a reaction against the rigid standards and historical subject matter of the French Académie des Beaux-Arts and its annual state-sponsored exhibition, the [Salon (Paris)]. According to The Met's Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, artists who would become the Impressionists found their official artistic training to be stifling. They were drawn to painting modern life and landscapes, often working outdoors (en plein air) to capture the transient effects of sunlight. The movement's precursors include the landscape painters of the Barbizon School and the Realist painter Gustave Courbet. The artist Édouard Manet is often considered a pivotal figure who bridged Realism and Impressionism, as his controversial paintings like Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe (1863) challenged academic conventions and inspired the younger generation of artists.

The First Impressionist Exhibition

The formal beginning of the movement is often dated to 1874, when a group of artists including Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, and Berthe Morisot formed the Société Anonyme Coopérative des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs to exhibit their work independently of the official Salon. As noted by the Musée d'Orsay, their first exhibition was held in April 1874 in the former studio of the photographer Nadar. The movement's name was coined derisively by the critic Louis Leroy in a review for the satirical magazine Le Charivari. He seized upon the title of Monet's painting, Impression, soleil levant (Impression, Sunrise), to mock the artists' work as mere unfinished sketches or "impressions."

Characteristics and Techniques

The core of Impressionist technique was the desire to capture a fleeting moment and the specific atmospheric conditions it contained. According to The National Gallery, London, this led to several distinct stylistic innovations:

- –Visible Brushstrokes: Artists used short, thick strokes of paint to quickly capture the essence of the subject, rather than blending and shading them to create a smooth surface. This technique created a textured effect and emphasized the artist's hand.

- –Emphasis on Light: The primary goal was to depict the changing qualities of light and reflection. Artists often painted the same scene multiple times at different hours of the day or in different seasons, as seen in Monet's Haystacks and Rouen Cathedral series.

- –Color: Impressionists often used a palette of pure, intense colors applied side-by-side with minimal mixing, allowing the viewer's eye to optically blend them. The use of complementary colors was common to create vibrant shadows and highlights, a departure from the traditional use of grey and black.

Britannica states that the development of new synthetic pigments in the 19th century provided artists with a wider and more brilliant range of colors.

- –Modern Subject Matter: The Impressionists turned away from historical, mythological, and religious themes. Instead, they depicted everyday life in and around Paris: bustling boulevards, cafés, theaters, riverside leisure, and domestic interiors. Their work provides a visual record of the social life of the late 19th-century bourgeoisie.

- –Composition: Influenced by the new art of photography and the aesthetics of Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints, Impressionists often used asymmetrical compositions, cropped figures, and unusual visual angles.

Key Artists

While the group was diverse, several figures are central to the Impressionist movement:

- –Claude Monet (1840–1926): Considered the quintessential Impressionist, he was dedicated to capturing nature's fleeting moments and the perception of light. His work Impression, soleil levant gave the movement its name.

- –Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919): Focused on the human figure, particularly female nudes and vibrant scenes of people in social settings, such as Bal du moulin de la Galette (1876).

- –Edgar Degas (1834–1917): A master draftsman, he is known for his depictions of ballerinas, horse races, and laundresses. Unlike many others, he preferred to work in a studio and rejected the en plein air label. He frequently worked in oil paint and pastel.

- –Camille Pissarro (1830–1903): The only artist to exhibit in all eight Impressionist exhibitions, he was a mentor to many younger artists. His work focused on rural landscapes and urban scenes.

- –Berthe Morisot (1841–1895): A leading female Impressionist, Morisot was celebrated for her intimate domestic scenes and portraits, often featuring women and children from her own social circle.

- –Alfred Sisley (1839–1899): A British painter who worked in France, he was one of the most consistent Impressionists, dedicating his career almost exclusively to painting landscapes en plein air.

Reception and Legacy

Initially, Impressionism was met with harsh criticism and ridicule from the art establishment and the public. As detailed by The Art Story Foundation, critics found the visible brushwork, unblended colors, and everyday subject matter to be shocking and unprofessional. However, by the 1880s, the movement began to gain acceptance, and the artists found commercial success through dealers like Paul Durand-Ruel.

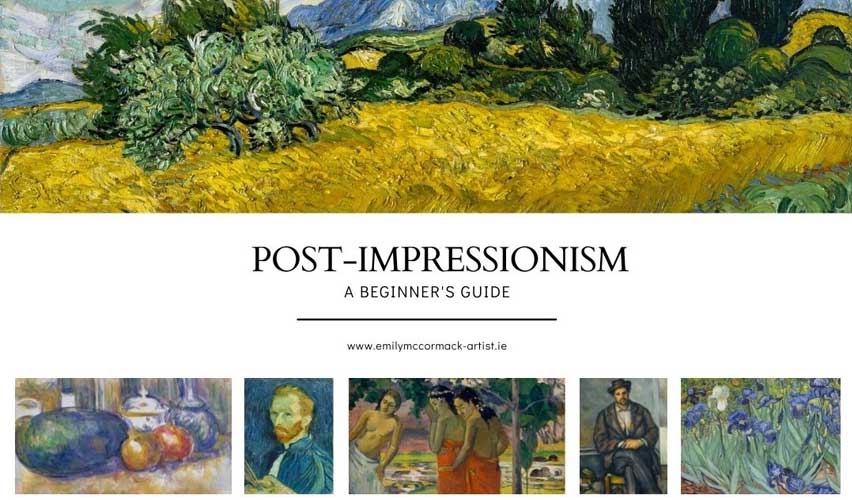

Impressionism fundamentally shifted the course of Western art. It broke the monopoly of state-sponsored academies and paved the way for artists to explore personal vision and technique. Its innovations in color, light, and form directly influenced subsequent art movements, most notably Post-Impressionism (led by artists like Cézanne, Van Gogh, and Gauguin), Fauvism, and early abstraction.