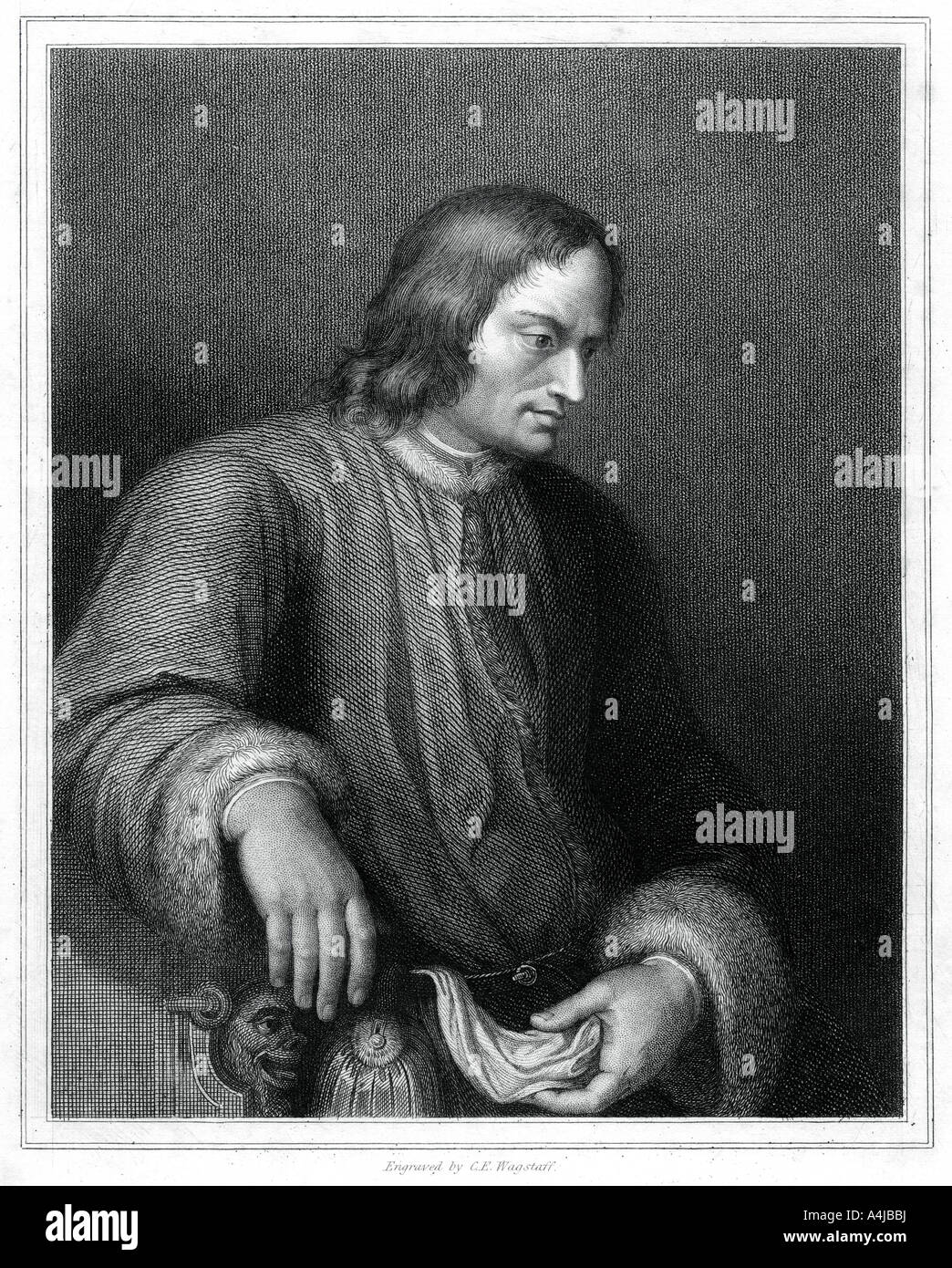

Lorenzo de' Medici (born 1 January 1449 in Florence, died 9 April 1492 at Careggi) was an Italian statesman, banker, poet, and de facto head of the Medici house whose patronage and diplomacy shaped the Florentine Renaissance, according to the Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Family and early life

Lorenzo was the son of Piero di Cosimo de' Medici and Lucrezia Tornabuoni and grandson of Cosimo de' Medici; he entered Florentine political bodies in his teens, including the balìa and the Consiglio dei Cento in 1466, as noted by the entry in the Enciclopedia Italiana Treccani. He married Clarice Orsini in 1469, forging ties with prominent Roman nobility, as recorded by

Treccani. Upon the death of his father in December 1469, he assumed leadership of Florence while formally remaining a private citizen, a dynamic emphasized by

Treccani and summarized by

Britannica.

Governance and institutions

Contemporaries and later historians described Lorenzo’s regime as that of a “benevolent tyrant” operating within a republican framework; he strengthened Medicean control through institutional adjustments, including creation of a Council of Seventy to supersede older councils, as detailed by Britannica. His approach balanced pageantry—festivals, tournaments, and civic spectacle—with carefully managed oligarchic consent, according to

Britannica and the Machiavellian perspective summarized in

Treccani’s Enciclopedia machiavelliana.

The Pazzi Conspiracy and war (1478–1480)

On 26 April 1478, members of the Pazzi family and their allies attacked Lorenzo and his brother Giuliano during High Mass in the cathedral; Giuliano was killed, and Lorenzo escaped with minor wounds, events reconstructed by Encyclopaedia Britannica and the Lorenzo biography at

Britannica. The failed coup triggered a papal-Florentine war; Pope Sixtus IV and King Ferrante (Ferdinand I) of Naples pressed Florence, whereupon Lorenzo personally traveled to Naples (December 1479–March 1480) and negotiated a settlement that isolated the papacy, as reported by

Treccani and distilled by

Britannica. The episode consolidated Lorenzo’s position and strengthened his image as the “needle on the Italian scales,” per

Britannica. These events are central to any account of the Pazzi Conspiracy, the most dramatic domestic challenge to Medicean rule, per

Britannica.

Diplomacy and the Italian balance of power

Through the 1480s, Lorenzo cultivated alliances with Italian states (notably Naples, Milan, and regional powers) and pursued territorial adjustments (e.g., acquisitions such as Pietrasanta and Sarzana) that reinforced Florence’s strategic position, a policy profile traced by Treccani. He participated in broader Italian conflicts—such as the War of Ferrara (1482–1484)—while maintaining Florentine equilibrium and prestige, as outlined by

Treccani and contextualized in the scholarship of John M. Najemy (book://John M. Najemy|A History of Florence 1200–1575|Blackwell|2006).

Patronage, humanism, and artistic circles

Lorenzo’s villas at Careggi, Fiesole, and Poggio a Caiano hosted a circle often called the “Platonic Academy,” centered on Marsilio Ficino with figures such as Angelo Poliziano and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, a milieu described by Britannica. Artists he supported or advanced included Giuliano da Sangallo, Sandro Botticelli, Andrea del Verrocchio, and Leonardo da Vinci; his household treated artists with unusual familiarity, according to

Britannica. Toward the end of his life he established a sculpture garden near San Marco, where a teenage Michelangelo came to his notice; Lorenzo brought the youth into his palace, a formative episode summarized by

Britannica’s Michelangelo entry and the Lorenzo biography at

Britannica. Michelangelo’s earliest reliefs—Madonna della Scala and Battle of the Centaurs—now in Casa Buonarroti, are documented by the museum’s own descriptions (

Casa Buonarroti: Madonna della Scala and

Casa Buonarroti itinerary).

Literary work

Beyond patronage, Lorenzo wrote extensively in Tuscan on themes ranging from love to civic festivity; works include the Canti carnascialeschi (e.g., “Trionfo di Bacco e Arianna”), Nencia da Barberino, and Selve d’amore, with his literary activity closely tied to humanist discourse, as synthesized by Treccani. His cultivation of Tuscan vernacular alongside Latin is highlighted in

Treccani and echoed by

Britannica.

Finance and the Medici bank

Under Lorenzo the Medici bank’s profitability declined amid wider European competition and managerial failures in key branches. The London, Bruges, and Lyon branches became insolvent in the 1470s–1480s, a pattern summarized by Britannica. Classic financial history by Raymond de Roover analyzes these failures—especially Tommaso Portinari’s Bruges management and royal-credit exposure—as structural causes of the bank’s collapse (book://Raymond de Roover|The Rise and Decline of the Medici Bank: 1397–1494|Harvard University Press|1963). While Lorenzo’s largesse strained family resources, allegations that he subsidized the bank with public funds are not supported by evidence, as stated by

Britannica and assessed in de Roover’s study (book://Raymond de Roover|The Rise and Decline of the Medici Bank: 1397–1494|Harvard University Press|1963).

Household, alliances, and church politics

Dynastic marriages and ecclesiastical preferment anchored Lorenzo’s strategies: his marriage to Clarice Orsini linked Florence to Roman baronial networks; a daughter, Maddalena, married Franceschetto Cybo, the son of Pope Innocent VIII; and at age 13 his son Giovanni received a cardinal’s hat from Innocent VIII, facts reported by Britannica. After Giuliano’s murder in 1478, Giulio de’ Medici (the future Pope Clement VII), an illegitimate son of Giuliano, was reared in Lorenzo’s household, per

Britannica’s Clement VII entry. These arrangements illustrate the interweaving of Florentine and curial politics that characterized his leadership, as discussed in Najemy’s synthesis (book://John M. Najemy|A History of Florence 1200–1575|Blackwell|2006).

Religion and reformers

In 1490 Lorenzo, on the recommendation of Pico della Mirandola, permitted the Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola to preach in Florence; Savonarola’s later denunciations of Medici worldliness and prophecy of imminent judgment gained traction as Lorenzo’s health waned, according to Britannica. A later tradition holds that Savonarola demanded political concessions at Lorenzo’s deathbed, but the historicity of that exchange is doubtful, a caution noted by

Britannica.

Death, burial, and immediate aftermath

Lorenzo died on 9 April 1492 at the villa in Careggi, aged 43, and was buried in San Lorenzo; his modest tombstone stands apart from Michelangelo’s later monuments to Medici kinsmen in the New Sacristy, as described by Britannica. Within two years, a republican movement allied with Savonarola expelled the Medici from Florence (1494), placing Lorenzo’s son Piero in exile and interrupting Medicean dominance until 1512, a political sequence framed in

Britannica and broader Florentine histories (book://John M. Najemy|A History of Florence 1200–1575|Blackwell|2006).

Assessment and historiography

Early modern authors such as Francesco Guicciardini and Niccolò Machiavelli offered contrasting profiles of Lorenzo as a prudent “prince” within a republic versus a master of oligarchic control; modern scholarship similarly balances his cultural achievements with recognition of tightened political structures, as surveyed in Treccani’s Enciclopedia machiavelliana and summarized by

Britannica. His cultural program—rooted in humanist sociability, vernacular literature, and artist patronage—made Florence a model of late Quattrocento civic culture, while his finance and statecraft navigated, but could not resolve, shifting Italian power politics, a synthesis consistent with de Roover’s financial analysis (book://Raymond de Roover|The Rise and Decline of the Medici Bank: 1397–1494|Harvard University Press|1963) and Najemy’s political history (book://John M. Najemy|A History of Florence 1200–1575|Blackwell|2006).