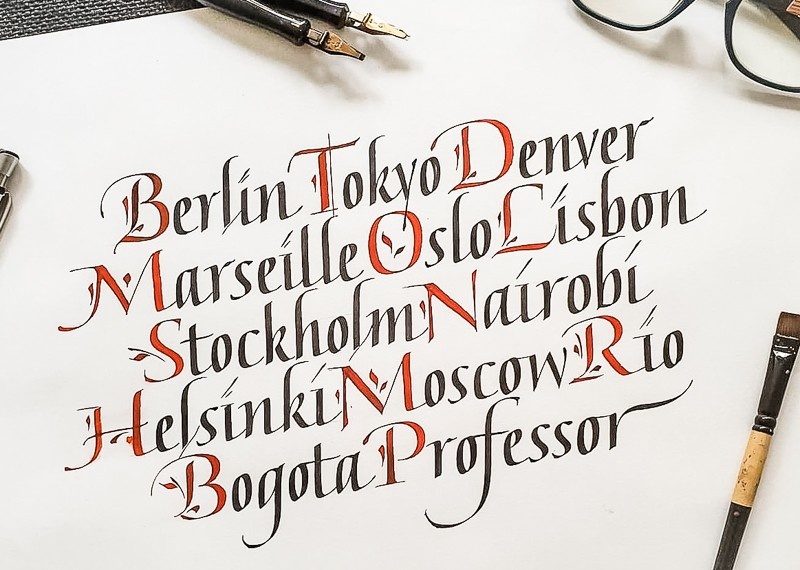

Calligraphy is the art of beautiful, stylized writing, from the Greek kallos (beauty) and graphein (to write), emphasizing proportion, rhythm, and the skillful formation of letters with pen or brush and ink. According to Encyclopaedia Britannica, it has been regarded as a major art form in regions such as East Asia and the Islamic world, with deep historical traditions and codified techniques.

Tools and materials

- –East Asia: The core implements, often called the “Four Treasures of the Study” (brush, inkstick, paper, inkstone), enable subtle modulation of line and tone; ink is ground from solid sticks on an inkstone, then applied with a soft hair brush to absorbent papers to produce a wide range of effects. The Metropolitan Museum of Art notes how varying brush pressure, speed, and ink load yields characteristic textures and spatial rhythms in Chinese practice (

The Met – Chinese Calligraphy;

The Met – Essay excerpt).

- –Latin West: Medieval scribes typically wrote on parchment or vellum with quills; black inks were commonly made from oak galls (iron-gall ink) with gum arabic as binder. The Getty outlines parchment preparation and quill writing in its overview of medieval bookmaking (

Getty – The Making of a Medieval Book), and the University of Nottingham summarizes common ink recipes used by European scribes (

University of Nottingham – Materials).

Historical development by region

East Asia

Chinese calligraphy developed canonical script families—Seal, Clerical (official), Regular, Running, and Cursive—practiced as a literati art tied to moral cultivation and brush technique. Chinese calligraphy is documented from early imperial periods and is central to painting and scholarship; The Met details the expressive range achieved through brush and ink and the literati valuation of spontaneity and form (

The Met – Chinese Calligraphy). In recognition of its cultural significance, “Chinese calligraphy” was inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2009 (

UNESCO listing).

Japanese and Korean traditions adapted the brush-and-ink aesthetics to local scripts and contexts (kana, kanji; hangul and hanja), integrating poetry, religion, and court culture; museum and scholarly essays at The Met emphasize the longstanding interrelations among poetry, painting, and calligraphy in Japan (The Met – Islamic and East Asian calligraphy overview for educators).

Islamic world

Calligraphy is considered the most esteemed visual art of Islamic cultures, owing to the centrality of the Qur’an and the visual potential of the Arabic script. The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline explains how inscriptions adorn media from manuscripts to architecture, often uniting devotional and ornamental functions (The Met – Calligraphy in Islamic Art). Proportioned scripts were theorized by

Ibn Muqla (886–940), whose system used the rhomboid dot (nuqta), the height of the alif, and a governing circle to standardize letterforms; later refined by

Ibn al-Bawwāb (d. 1022/1031). Scholarly analysis of these proportional systems—including the role of the dot and circle—appears in a PLOS ONE study of mathematical concepts in Arabic calligraphy (

PLOS ONE). Britannica’s overview identifies the evolution from Kūfic to round scripts such as naskh, thuluth, muḥaqqaq, and rayḥānī (

Britannica – Arabic calligraphy).

Latin West

In the Latin-script tradition, late antique and medieval hands developed from Roman models through Insular and continental varieties. Insular script flourished in early medieval Britain and Ireland, while the Carolingian educational reforms under Charlemagne standardized a clear, legible book hand—

Carolingian minuscule—that later inspired Renaissance humanist roman and italic types. From the 12th century, compressed vertical “black letter” (Gothic) scripts became dominant in parts of Europe (

Britannica – Black letter). The advent of printing did not end handwriting; rather, it coexisted and cross-influenced, with roman and italic types deriving from humanist scripts (

Britannica – Calligraphy overview).

Revival, typography, and modern practice

The 19th–20th century revival, associated with the Arts and Crafts movement, emphasized historical techniques with the broad-edged pen. The British calligrapher Edward Johnston designed the pioneering sans-serif “Johnston” alphabet for the London Underground in 1916, often cited as the first modern sans based on classical proportions; Britannica profiles his role in modern calligraphy and lettering pedagogy (Britannica – Edward Johnston). The Victoria and Albert Museum holds Johnston’s original design drawings for Underground lettering (

V&A collection record), and Transport for London adopted an updated Johnston100 for contemporary media in 2016 (

Wired report).

Pointed-pen traditions such as English Roundhand (copperplate) and American Spencerian influenced business and ornamental penmanship in the 18th–19th centuries and remain actively taught. The International Association of Master Penmen, Engrossers and Teachers of Handwriting (IAMPETH) documents historical exemplars and promotes education in scripts like Copperplate and Spencerian (IAMPETH – About).

Techniques, form, and aesthetics

- –Proportion systems: In Islamic calligraphy, proportional rules (al-khaṭṭ al-mansūb) relate letterforms to the dot, alif height, and a governing circle, a framework traced to

Ibn Muqla and elaborated by later masters; recent scholarship models these relationships mathematically (

PLOS ONE).

- –Brush dynamics: In East Asia, expressive modulation comes from brush angle, pressure, and ink gradation; The Met details how variations in ink load and stroke create spatial energy and texture (

The Met – Chinese Calligraphy).

- –Broad-edged pen: In the Latin tradition, the nib’s cut and angle govern stroke contrast and texture; the Getty demonstrates how quill preparation and ruling structure the page, while inks and pigments shape color and illumination (

Getty – The Making of a Medieval Book).

Cultural roles and uses

Calligraphy functions as scripture transmission, state and personal correspondence, devotional and poetic art, and architectural or decorative inscription. The Met’s overview of Islamic art emphasizes the integration of writing with ornament across media (The Met – Calligraphy in Islamic Art). UNESCO recognizes “Chinese calligraphy” as intangible cultural heritage for its educational, ceremonial, and artistic roles throughout society (

UNESCO listing).

Notable figures and topics

- –Ibn Muqla (Abū ʿAlī Muḥammad ibn ʿAlī ibn Muqlah; 886–940), theorist of proportioned Arabic scripts; Britannica profile (

Britannica).

- –Ibn al-Bawwāb (d. 1022/1031), Abbasid-era master who refined round scripts and produced numerous Qur’ans; Britannica profile (

Britannica).

- –Carolingian minuscule, standardized under Carolingian reforms; later basis for humanist roman type (

Britannica).

- –Chinese calligraphy, canonical script families with literati aesthetics (

Britannica).

- –Islamic calligraphy, esteemed visual art of the Islamic world with codified scripts and ornament (

The Met).

- –Edward Johnston, central to the modern calligraphy revival and the 1916 Underground alphabet (

Britannica;

V&A).