Enceladus is a mid-sized icy moon of Saturn, approximately 504–505 km (≈313–314 mi) in diameter, with a mean radius near 252 km and a mass of about 1.08×10^20 kg. It is one of the most reflective objects in the Solar System, returning roughly 99% of incident visible light, and has typical surface temperatures near −201 °C. Enceladus orbits Saturn at about 238,000 km, completes one orbit in 32.9 hours, and keeps the same face toward the planet (synchronous rotation). Its brilliant albedo, compact size, and rapid orbital period are documented in NASA’s mission profiles and data sheets. (Enceladus overview: NASA Science; reflectivity:

NASA/JPL Photojournal, PIA10500; size:

NASA/JPL Photojournal, PIA07724; bulk parameters:

NSSDC Saturnian Satellite Fact Sheet).

Origins and naming

Enceladus was discovered on August 28, 1789, by William Herschel. The name, drawn from a Giant of Greek myth, was suggested by his son John Herschel in the 19th century following established conventions for Saturnian satellites. (Discovery and naming background: NASA History; overview:

NASA Science).

Orbital dynamics and environment

The moon follows a nearly circular path within Saturn’s E ring and is locked in a 2:1 mean-motion resonance with Dione, a configuration that maintains a small orbital eccentricity and drives tidal heating. Enceladus is the principal source of material for the E ring; particles escaping its plumes replenish that diffuse ring. (Orbit, resonance, and ring supply: NASA Science).

Surface and geology

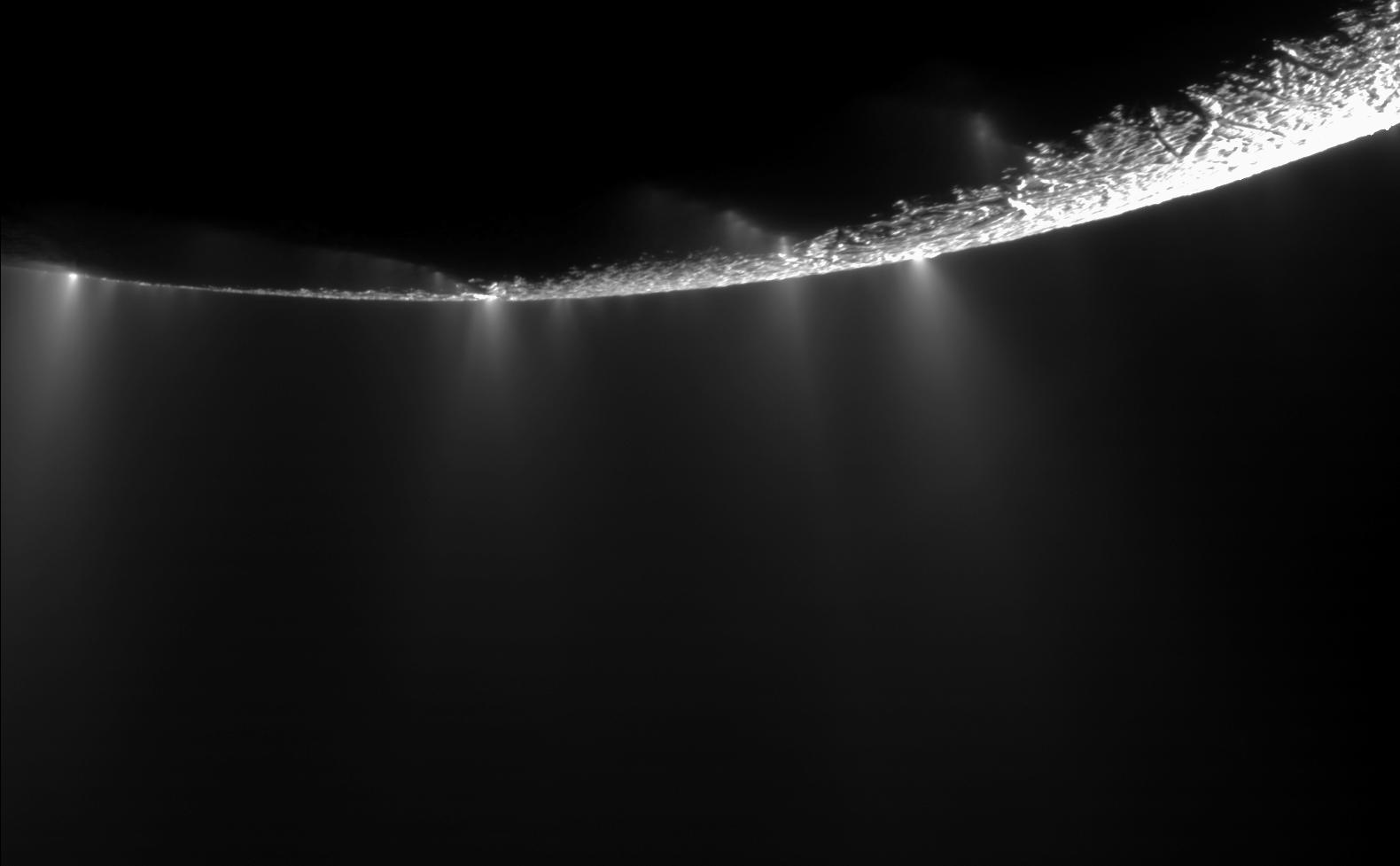

Voyager-era imaging and, later, the Cassini–Huygens mission revealed diverse terrains: older cratered regions, tectonized plains, and the distinctive south polar terrain almost devoid of impact craters. The south pole is crosscut by four prominent, roughly parallel fractures—informally the “tiger stripes”—named Alexandria, Cairo, Baghdad, and Damascus sulci. These fractures host warm vents that source the plumes. (Geologic diversity and south polar terrain: NASA Science; tiger stripe nomenclature and imagery:

NASA Science, PIA08835,

PIA11113,

PIA11114).

Thermal emission and tidal heating

Infrared measurements from Cassini’s Composite Infrared Spectrometer revealed unexpectedly high heat flow from the south polar terrain—on the order of tens of gigawatts in some analyses—challenging models that rely solely on eccentricity tides. The 2011 analysis reporting ≳15 GW underscores vigorous endogenic activity concentrated along the tiger stripes. (Thermal power and implications: JPL News).

Subsurface ocean and interior

Gravity-field measurements from Cassini flybys initially indicated a regional sea beneath the south polar terrain, with mass anomalies consistent with liquid water beneath 30–40 km of ice. Subsequent analyses, including Cassini’s detection of a subtle physical libration, pointed to a global ocean beneath the ice shell. NASA announced global-ocean evidence in 2015; current syntheses infer an ice shell averaging roughly 20–25 km thick, thinning to a few kilometers at the south pole. (South polar sea: ESA Science summary of Iess et al., Science 2014; global ocean announcement:

NASA News Release; shell thickness context:

NASA Science).

Plumes and composition

Cassini directly sampled the south polar plumes during multiple flybys after their discovery in 2005, measuring ejecta speeds near 400 m/s and determining that the gas is dominated by H₂O with contributions from CO₂, CH₄, NH₃, and other species; salts and silica were found in ice grains. (Plume discovery, composition, and velocities: NASA Science).

Evidence for hydrothermal activity comes from nanometer-scale silica particles requiring water–rock interaction at temperatures ≳90 °C, implying seafloor hydrothermal systems transporting material rapidly from the core–ocean interface to the surface. (Silica nanoparticles and temperature constraint: ESA Science summary of Hsu et al., Nature 2015).

Habitability indicators and ocean chemistry

During Cassini’s deepest plume transit (October 28, 2015), the Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer detected molecular hydrogen (H₂) at levels consistent with ongoing water–rock reactions (e.g., serpentinization) that provide chemical energy to potential metabolisms. The 2017 Science report interpreted the H₂ as evidence of thermodynamic disequilibrium favoring methanogenesis in the ocean. A NASA analysis based on Cassini measurements summarizes the plume gas as ≈98% H₂O, ≈1% H₂, with CO₂, CH₄, and NH₃ in smaller amounts. (Molecular hydrogen and implications: Science via PubMed; plume gas fractions:

NASA resource, PIA21442).

In 2023, a Nature study reported sodium phosphates in E‑ring ice grains sourced from Enceladus, indicating that orthophosphate is readily available in the ocean at concentrations at least 100× those of Earth’s oceans—removing a prior uncertainty about phosphorus availability among the canonical “CHNOPS” elements. (Phosphorus finding: Nature via PubMed). Later, a Nature Astronomy study (Dec. 14, 2023) reported strong evidence for hydrogen cyanide and additional oxidized organics in Cassini data, suggesting multiple, potentially energetic redox pathways in the ocean. (HCN and energy sources:

NASA Mission Update).

Remote observations and plume scale

In May 2023, the James Webb Space Telescope mapped a water-vapor plume extending more than 6,000 miles (≈9,600 km) from Enceladus, providing a system-scale view of how the moon’s emissions feed Saturn’s environment and rings. (JWST plume mapping: NASA Webb feature).

Exploration history

Voyager 2 provided the first close views in 1981, revealing geologic complexity. Cassini (2004–2017) executed numerous targeted flybys, discovered and repeatedly sampled the plumes, mapped the surface at high resolution, and constrained Enceladus’s interior and heat flow. A late-mission flyby (“E‑21”) in 2015 passed within ~49 km of the south pole to maximize in situ sampling of plume gases and ice grains. (Mission overview and plumes: NASA Science; flyby objectives:

NASA Science flyby brief).

Future missions and priorities

The U.S. Planetary Science and Astrobiology Decadal Survey (2023–2032) identifies an Enceladus “Orbilander” as the second-highest-priority new Flagship mission for initiation in the decade—an architecture to orbit Enceladus, analyze fresh plume material, then land to perform life detection and geophysical investigations. (National Academies summary and recommendation: NAP Chapter 22,

Planetary Decadal portal).

Location and context in the Saturn system

Enceladus resides between the orbits of Mimas and Tethys, embedded in the densest portion of the E ring that its plumes sustain. Its ongoing cryovolcanism, coupled with resonant tidal forcing by Dione, distinguishes it among ocean worlds such as Europa and positions it as a prime target for astrobiology. (Orbital setting and resonance: NASA Science; general reference:

Britannica).