Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) comprises techniques, interfaces, and governance practices that render the behavior and outputs of Artificial intelligence systems—especially those based on Machine learning—understandable to human users and stakeholders. In common usage, interpretability often denotes a human’s ability to ascribe meaning to a model’s outputs, while explainability emphasizes communicating reasons or mechanisms behind outputs, tailored to a user’s goals and context, distinctions articulated in guidance from the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). According to NIST’s Four Principles of Explainable AI and its companion report on psychological foundations, effective explanations should be accompanied by evidence, be meaningful to the audience, faithfully reflect the system’s process, and indicate conditions for appropriate use. NIST (Four Principles of Explainable AI, NISTIR 8312);

NIST (Psychological Foundations of Explainability and Interpretability in AI, NISTIR 8367). (

nist.gov)

History and scope

- –Early expert systems in the 1980s produced rule‑based “why” and “how” traces, but the recent drive for XAI arose with complex, statistically powerful models—especially deep architectures under the Neural network paradigm—that are accurate yet opaque. A widely cited U.S. programmatic catalyst was DARPA’s Explainable AI (XAI) research program (2017–2021), which funded new explainable models, human‑factors studies, and evaluations across analytics and autonomy.

DARPA (Explainable Artificial Intelligence program);

Gunning & Aha, “DARPA’s Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) Program,” AI Magazine (2019). (

darpa.mil)

- –Scholarly syntheses have mapped the field’s taxonomies, goals, and challenges, emphasizing human‑centered evaluation and the diversity of explanation recipients (developers, operators, decision subjects).

Barredo Arrieta et al., Information Fusion (2020);

Mohseni, Zarei & Ragan, ACM TiiS (2021). (

colab.ws)

Core concepts and terminology

- –Ante‑hoc (inherently interpretable) approaches constrain model structure to be understandable by design (e.g., sparse linear models, decision trees, generalized additive models), while post‑hoc explanations analyze a trained model to produce human‑readable rationales for predictions or behaviors. Overviews by NIST and foundational position papers distinguish interpretability and explainability and argue for rigorous, human‑grounded evaluation.

NISTIR 8312;

Doshi‑Velez & Kim (2017). (

nist.gov)

- –The literature highlights multiple explanation goals: debugging and model selection, regulatory reasons for adverse actions, contestability and recourse, risk communication, and appropriate trust calibration for different audiences. Representative frameworks stress matching explanation type to user needs and decision stakes.

Mohseni, Zarei & Ragan (2021);

NISTIR 8367. (

par.nsf.gov)

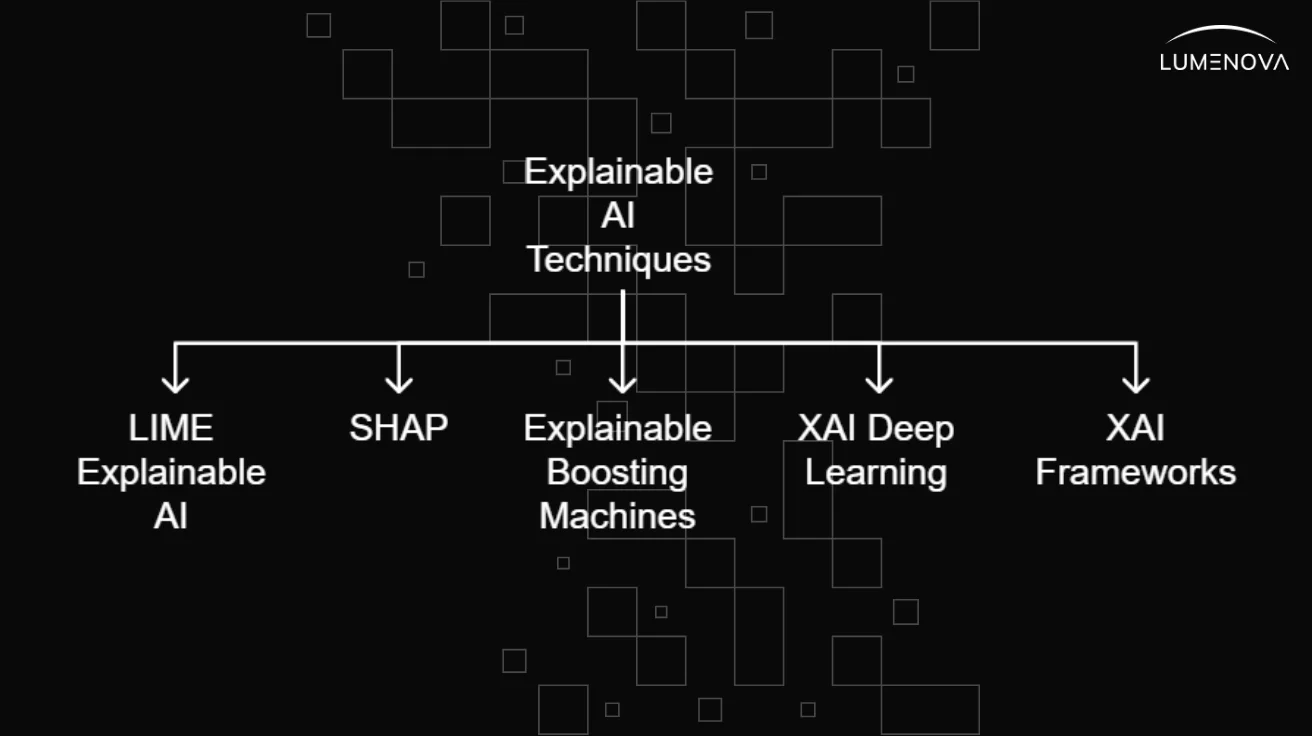

Representative methods

- –Local surrogate explanations approximate a complex model in the neighborhood of an instance, as in LIME, which learns a sparse linear proxy to explain individual predictions.

Ribeiro, Singh & Guestrin, “Why Should I Trust You?” KDD 2016. (

arxiv.org)

- –Additive feature attribution methods unify several techniques under axiomatic properties using Shapley values; SHAP provides theoretically justified local attributions and efficient variants for trees and deep models.

Lundberg & Lee, NeurIPS 2017. (

papers.nips.cc)

- –Gradient‑based visual explanations localize evidence in inputs for convolutional models; Grad‑CAM highlights salient regions supporting a class prediction and is widely used in vision tasks.

Selvaraju et al., ICCV 2017;

Simonyan et al., 2013. (

openaccess.thecvf.com)

- –Data‑centric explanations trace predictions to influential training points using influence functions to support debugging and data quality assessment.

Koh & Liang, ICML 2017. (

proceedings.mlr.press)

- –Counterfactual explanations communicate “what minimal changes would have yielded a different outcome,” offering actionable recourse without revealing model internals.

Wachter, Mittelstadt & Russell (2017). (

turing.ac.uk)

- –The interpretability literature also proposes rule‑based anchors, concept activation, and decomposition methods, alongside tutorials and books for practitioners.

Ribeiro et al., “Anchors,” AAAI 2018;

Molnar, Interpretable Machine Learning (3rd ed., 2025). (

scinapse.io)

Evaluation, usability, and pitfalls

- –NIST’s principles emphasize that explanations should reflect the system’s actual reasoning process (fidelity) and be meaningful to specific users; workshops and reports connect psychological factors (e.g., user goals, mental models) to explanation design.

NISTIR 8312;

NISTIR 8367. (

nist.gov)

- –Human‑centered surveys propose goal‑method mappings and multi‑stakeholder evaluation, including task performance, trust calibration, and usability studies.

Mohseni, Zarei & Ragan, ACM TiiS (2021). (

par.nsf.gov)

- –Empirical critiques warn that some saliency maps may be insensitive to model or data, underscoring the need for “sanity checks” and rigorous validation; attention weights can be manipulated to produce deceptive rationales.

Adebayo et al., NeurIPS 2018;

Pruthi et al., 2019. (

papers.nips.cc)

- –A prominent viewpoint argues that for high‑stakes decisions, inherently interpretable models are preferable to post‑hoc explanations of black‑box models.

Rudin, Nature Machine Intelligence (2019). (

scholars.duke.edu)

Law, policy, and standards

- –In the European Union, transparency and interpretability duties for high‑risk systems are codified in the EU AI Act, which entered into force on 1 August 2024 and phases in requirements including instructions for use, human oversight, and the ability for deployers to interpret outputs.

European Commission news release (Aug. 1, 2024);

Recital 72 and Article 13 summaries. (

commission.europa.eu)

- –The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) addresses automated decision‑making in Article 22, ensuring safeguards such as the right to obtain human intervention, express one’s view, and contest decisions, which motivates explanation practices in EU settings.

GDPR Article 22 (text portals). (

gdpr.org)

- –In U.S. credit markets, the Equal Credit Opportunity Act and Regulation B require “specific reasons” in adverse action notices, regardless of whether decisions use complex or “black‑box” models; the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has clarified this for AI‑based credit decisions.

CFPB Circular 2022‑03;

12 CFR § 1002.9 (Regulation B). (

consumerfinance.gov)

- –U.S. federal guidance outside of sectoral laws includes the White House Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights, which articulates “Notice and Explanation” and “Human Alternatives” as design principles for automated systems.

White House OSTP, Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights—Notice and Explanation. (

bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov)

- –International standards bodies have published risk and management frameworks that reference explainability within trustworthy AI, including ISO/IEC 23894 (AI risk management), ISO/IEC 42001 (AI management systems), and ISO/IEC TR 24028 (trustworthiness).

ISO/IEC 23894:2023;

ISO/IEC 42001:2023;

ISO/IEC TR 24028:2020. (

iso.org)

Applications and domains

- –XAI methods are widely employed in domains such as vision, language, healthcare, and finance for auditing, safety analysis, decision support, and scientific insight. Reviews document technique families, best‑practice usage, and case studies, especially for deep learning.

Samek et al., Proceedings of the IEEE (2021);

Selvaraju et al., ICCV 2017. (

arxiv.org)

Tooling and open resources

- –Publicly available toolkits, tutorials, and open‑source libraries support LIME, SHAP, saliency, and influence‑function analyses, alongside practitioner guides consolidating design choices and caveats.

Lundberg & Lee, NeurIPS 2017 (paper site);

Koh & Liang, ICML 2017 (PMLR);

Molnar, Interpretable Machine Learning. (

papers.nips.cc)