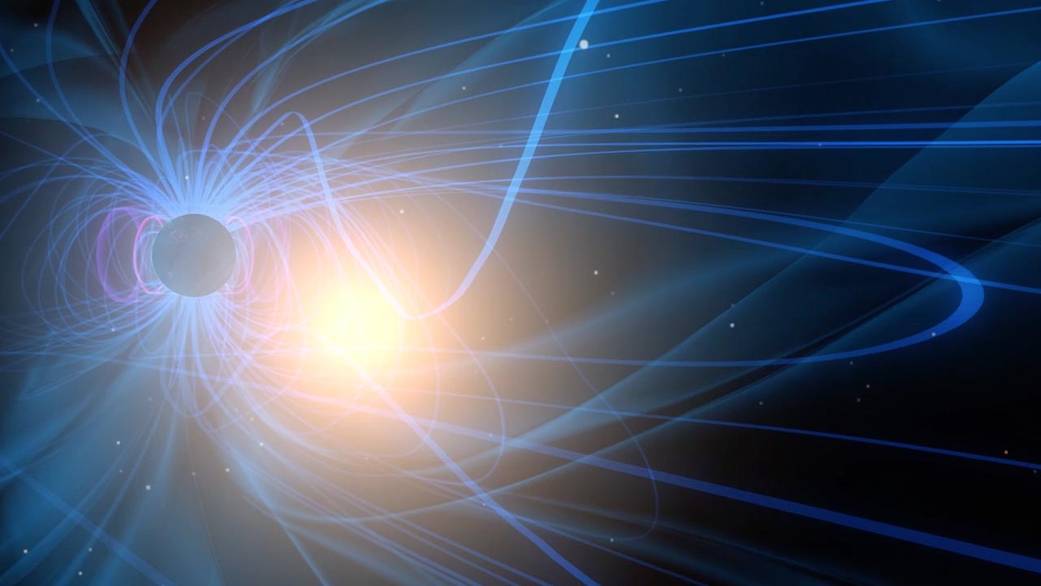

Magnetic reconnection is a plasma-physics process in which magnetic field topology changes and magnetic energy is rapidly converted into bulk flows, heating, and non-thermal particles in highly conducting plasmas. It occurs across natural and laboratory environments and governs key space-weather and astrophysical phenomena, including Solar flare eruptions and energy transfer into Earth’s Magnetosphere. According to a comprehensive review, reconnection is intrinsically multi‑scale, coupling magnetohydrodynamic dynamics to kinetic scales where field lines effectively “break” and rejoin (Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010;

Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 2009).

Historical development

Early theoretical treatments identified how the “frozen‑in” condition of ideal Magnetohydrodynamics fails in thin current sheets, enabling reconnection. The resistive MHD framework of the Sweet–Parker model (1950s) explained slow reconnection through a long, thin diffusion region, while Petschek (1960s) proposed a faster configuration with standing slow-mode shocks and a short diffusion region (Priest & Forbes, Cambridge University Press;

NASA NTRS/Petschek records). Modern work established that two‑fluid and kinetic effects, including the Hall term, enable fast reconnection rates inconsistent with classic Sweet–Parker scaling (

Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010). Time‑dependent fragmentation of long current sheets into plasmoids (secondary islands) further accelerates reconnection in high‑Lundquist‑number systems (

Loureiro & Uzdensky 2015).

Physical mechanisms and theory

In ideal MHD, Alfvén’s frozen‑in theorem constrains field lines to move with the plasma; reconnection requires localized breakdown in a thin “diffusion region,” where non‑ideal terms in the generalized Ohm’s law become important and change field‑line connectivity (Britannica – Magnetic reconnection;

Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010). The electron diffusion region (EDR), nested inside the ion diffusion region, hosts intense currents and non‑gyrotropic electron dynamics that sustain the reconnection electric field and enable rapid energy conversion (

Science 2016 – Burch et al.).

Rates of fast reconnection in collisionless and asymmetric plasmas often normalize to an order‑of‑magnitude value near 0.1 when expressed relative to the upstream Alfvénic scale, consistent with theory, simulations, and in‑situ measurements (Liu et al. 2017;

Physics of Plasmas 2010 – Birn et al.). The detailed rate depends on upstream asymmetries, guide fields, plasma beta, and turbulence, but two‑fluid/Hall physics robustly facilitates electron‑scale decoupling and rapid outflows (

Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010).

In collisional regimes, the Sweet–Parker configuration predicts a narrow current sheet and slow reconnection set by resistive diffusion, whereas Petschek‑type fast reconnection invokes shocks and a compact diffusion region (Priest & Forbes;

NASA NTRS/Petschek). Many large‑scale systems evolve toward time‑dependent, plasmoid‑mediated reconnection that breaks the Sweet–Parker constraint and yields fast, bursty energy release (

Loureiro & Uzdensky 2015).

Environments and observational evidence

Reconnection drives explosive activity in the solar atmosphere. Standard flare models invoke the formation of a vertical current sheet above post‑flare loops; reconnection there produces hot loops, supra‑arcade downflows, and accelerated particles observable in X‑rays and EUV (Living Reviews in Solar Physics 2011 – Shibata & Magara). In the heliosphere, the Solar wind carries the interplanetary magnetic field (IMF), which reconnects with Earth’s field at the dayside magnetopause and in the magnetotail, driving convection and substorms; these global roles are well established in geospace research (

Britannica – Geomagnetic field: Magnetic reconnection).

Multi‑spacecraft missions resolved reconnection in situ. The four‑craft Magnetospheric Multiscale Mission (MMS; launched March 12, 2015) targets electron‑scale physics in the magnetopause and magnetotail, providing millisecond‑resolution measurements that captured the EDR and its energy conversion signatures (NASA Science – MMS;

Science 2016 – Burch et al.). MMS also revealed reconnection operating within highly turbulent magnetosheath plasma, extending where and how reconnection proceeds in geospace (

NASA – turbulent-space discovery;

NASA MMS 5‑year summary).

The European Space Agency’s Cluster constellation pioneered three‑dimensional mapping of reconnection at Earth, including direct electric‑field measurements near reconnection sites and observations of events within Kelvin–Helmholtz vortices at the magnetopause, revealing how boundary turbulence seeds mixing and reconnection (ESA Cluster overview;

ESA – magnetic bull’s‑eye;

ESA – reconnection in giant swirls).

Laboratory experiments provide controlled tests. The Magnetic Reconnection Experiment (MRX) at Princeton reproduced collisional reconnection regimes, quantified scalings, and illuminated two‑fluid physics; laboratory insights complement space and solar observations and benchmark theory (PPPL – MRX;

Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010).

Mathematical framework and key parameters

Reconnection is often introduced within resistive MHD via the induction equation, where a localized non‑ideal region permits field‑line slippage and topology change. The characteristic outflow speed is of order the Alfvén speed based on the reconnecting field, while the inflow speed and rate depend on the diffusion‑region geometry and microphysics. Two‑fluid and kinetic formulations resolve Hall currents, electron pressure‑tensor effects, and finite‑Larmor‑radius physics that determine the structure and extent of the ion and electron diffusion regions (Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010;

Priest & Forbes). In large‑S systems, current sheets are unstable to plasmoid formation, leading to chains of islands and effectively fast rates even in resistive MHD (

Loureiro & Uzdensky 2015).

Applications and significance

Reconnection regulates space‑weather impacts by controlling solar‑terrestrial coupling and the onset of geomagnetic storms and substorms, with direct technological relevance for power grids, navigation, and communications (NASA GSFC – About MMS;

Britannica – Geomagnetic field: Magnetic reconnection). In magnetic‑confinement fusion devices such as a Tokamak, unwanted reconnection triggers events like sawtooth crashes and edge instabilities that degrade performance; understanding and controlling reconnection is therefore vital to fusion research (

Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 2009;

Priest & Forbes).

Contemporary research directions

Current work addresses reconnection onset and transition between slow, collisional regimes and fast, collisionless/Hall regimes; the role of turbulence in enabling or modulating reconnection; and electron‑only reconnection at small scales in the solar wind and magnetosheath, all with implications for particle acceleration and energy partition in space and astrophysical plasmas (Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 2009;

NASA – turbulent-space discovery;

NASA MMS 5‑year summary).