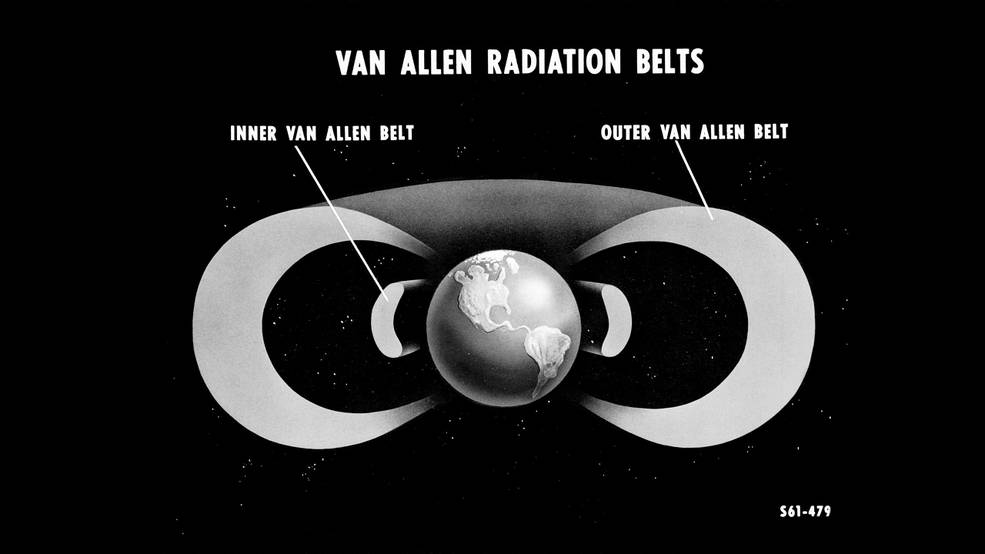

The Van Allen radiation belts are regions of energetic protons and electrons confined by Earth's magnetosphere and organized into two persistent, roughly toroidal zones encircling the planet. The belts were identified in 1958 from instruments led by James Van Allen on the U.S. satellite Explorer 1, establishing a foundation for modern magnetospheric physics and space weather studies (NASA JPL;

NASA History).

Physical structure and composition

- –Two main zones are recognized: an inner belt, centered roughly a few thousand kilometers above Earth, and an outer belt extending to several Earth radii. Typical altitude ranges are approximately 1,000–12,000 km for the inner belt and 13,000–60,000 km for the outer belt, though boundaries vary with geomagnetic conditions (

Britannica).

- –The inner belt is dominated by high‑energy protons (tens to hundreds of MeV) produced largely by the cosmic‑ray albedo neutron decay (CRAND) mechanism; electrons are present but generally at lower energies. Reviews of observations and theory of CRAND and inner‑belt protons remain consistent with early and subsequent analyses (

NTRS/Reviews of Geophysics, 1973;

Phys. Rev. Lett., 1972).

- –The outer belt is dominated by relativistic electrons (hundreds of keV to several MeV) whose intensity varies strongly with the Solar wind and geomagnetic activity (

NASA Science;

Britannica).

- –The belts often display a “slot region” of reduced electron flux between them, maintained primarily by wave‑driven loss (plasmaspheric hiss) inside the plasmasphere (

JGR 2007;

JGR 1973;

Nature 2015).

Particle motion, coordinates, and variability

- –Trapped particles execute gyromotion, bounce between mirror points, and drift azimuthally, conserving adiabatic invariants under quasi‑static conditions. Mapping and comparison of measurements commonly use the McIlwain L‑parameter, introduced to organize trapped‑particle distributions along magnetic shells (

JGR 1961;

SPENVIS background).

- –Belt intensities and boundaries evolve with geomagnetic activity and Geomagnetic storm phases, driven by coupling with the solar wind and interplanetary magnetic field (

Britannica—space weather;

NASA Science).

Sources, acceleration, and loss processes

- –Inner‑belt protons: Predominantly supplied by CRAND, wherein cosmic rays produce atmospheric neutrons whose beta decay injects protons into confined drift shells (

NTRS/Reviews of Geophysics, 1973;

Phys. Rev. Lett., 1972).

- –Outer‑belt electrons: Local acceleration by whistler‑mode chorus waves can rapidly energize seed populations to MeV energies on timescales of hours, as shown with Van Allen Probes data and modeling of storms in 2012–2013 (

Nature 2013;

JGR 2014).

- –Loss mechanisms: Electromagnetic ion cyclotron (EMIC) waves can precipitate relativistic electrons into the atmosphere, and magnetopause shadowing/radial diffusion remove electrons outward; inside the plasmasphere, hiss scattering maintains the slot region (

JGR 2017;

JGR 2015—EMIC event;

JGR 1973; OSTI;

Space Science Reviews 2017).

Transient additional belts and extreme events

- –In September 2012, an isolated, long‑lived third belt of >2 MeV electrons formed and persisted for weeks, revealed by the twin Van Allen Probes; this “storage ring” was later disrupted by an interplanetary shock (

Science 2013 via OSTI;

UNH repository).

- –During the major May 2024 storm, a NASA CubeSat observed two new temporary belts—one including a distinct proton population—between the permanent belts; these belts decayed with subsequent storms, providing new constraints on storm‑time dynamics (

NASA Science, Feb. 6, 2025).

Regional features: South Atlantic Anomaly (SAA)

- –Because Earth’s magnetic dipole is offset and tilted, the inner belt approaches Earth most closely over the South Atlantic, creating the South Atlantic Anomaly. Satellites transiting the SAA experience elevated radiation, necessitating operational mitigations (e.g., instrument safing) and robust shielding (

ESA Swarm).

Discovery and major missions

- –Explorer 1 (launched January 31, 1958) carried Van Allen’s Geiger counter experiment and produced the data leading to the belts’ discovery; Explorer 3, Explorer 4, and Pioneer 3 refined early maps (

NASA JPL;

NASA History).

- –The 2012–2019 Van Allen Probes mission provided definitive in‑situ measurements of fields and particles that transformed understanding of acceleration and loss, including the 2012 transient third belt and inner‑belt electron variability (

NASA;

NASA).

Spacecraft hazards and engineering considerations

- –Energetic electrons (“killer electrons”) and protons in the belts can cause single‑event effects, deep dielectric charging, and solar array/sensor degradation. Spacecraft design includes component hardening, shielding, and operational strategies (e.g., powering down sensitive instruments in peak regions). Belt variability during Geomagnetic storm conditions is a key driver of risk (

Britannica—space weather;

NASA Science overview).

Comparative planetary context and theory

- –Analogous trapped radiation belts exist at strongly magnetized planets (e.g., Jupiter, Saturn), with differences arising from magnetic moments, plasma sources, and moon/ring interactions; CRAND and wave‑particle processes are also implicated beyond Earth (

NTRS—Jupiter, 1974;

NTRS—Saturn, 1980).

- –Foundational treatments of trapped‑particle motion, adiabatic invariants, and diffusion underpin modern belt models and forecast systems (book://M. Walt|Introduction to Geomagnetically Trapped Radiation|Cambridge University Press|1994; book://M. G. Kivelson & C. T. Russell (eds.)|Introduction to Space Physics|Cambridge University Press|1995).

Terminology and mapping

- –“L‑shell” (McIlwain L) denotes the equatorial crossing distance in Earth radii of a magnetic field line; it organizes observations by drift shell, aiding comparison across missions and epochs (

JGR 1961).

Explorer 1: Internal James Van Allen: Internal Earth's magnetosphere: Internal Solar wind: Internal Van Allen Probes: Internal Geomagnetic storm: Internal South Atlantic Anomaly: Internal